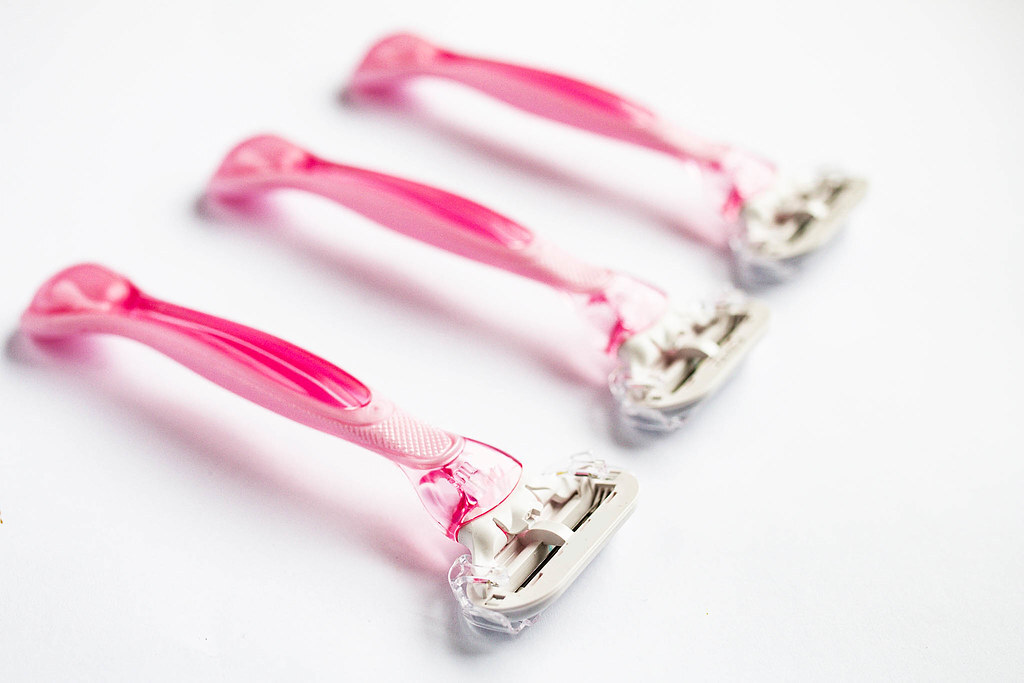

A pink razor. What might seem like a simple object, can tell us a lot about gender inequality. In 2014, a French feminist collective, Georgette Sand, discovered that Monoprix (a French retail chain) was selling a pack of five disposable pink razors for €1.80 and a pack of ten blue disposable razors for €1.72. This highlighted the gender inequality within product pricing. In November 2014, following the success of the group’s petition to stop the higher pricing of women’s products solely based on their colour, the French secretary of state for women’s rights, Pascale Boistard, asked a very important question “Le rose est-il une couleur de luxe?” (Is pink a luxury colour?). This observation is not just limited to France as already in 2011, the University of Central Florida has discovered that women pay more for cosmetic products such as deodorants. The term Pink Tax has come after these discoveries to describe not an actual tax but rather the gender-based pricing that is the result of the design of products aimed towards women often being pink.

Historically, pink was not always perceived as a feminine colour. In the West, from the mid – 18th century pink was worn by both men and women as a symbol of luxury and class. In fact, pink was seen to be more masculine than feminine as it was thought to be a paler shade of red which had more masculine undertones with military associations. This perception altered from the mid-19th century when the feminization of pink began. With the invention of industrially produced dyes, a bigger variety of colours was available and pink was no longer a status symbol, but rather a symbol of delicacy, often attributed to females. At the beginning of the 20th century colours increasingly began to be used as a branding tool, and in the following decades, the gradual shift of the meaning of the colour pink was happening. It was in 1950s America that pink has become much more attributed to females than ever before. The branding and marketing industries of post-war America made pink more gender-coded with it being shown as an appropriate colour for women’s products such as kitchen appliances. The idea of pink is for girls and blue is for boys was fully born.

More recently, pink has gone through a period of being a very popular colour among both sexes, with the Pantone Colour Institute even making it one of its Colours of the Year in 2016. Pink has an incredibly important social, cultural and political value and has been subverted and reclaimed by queer communities as well as used as a symbol of the feminist movement among many other things. However, it is important to highlight that the meanings of colours and their gender associations change depending on the culture that they are used in.

On the other hand, the pink razor can also tell us a lot about the social pressures that have been and still are put on women to remove their body hair. In 1901, the safety razor was invented by Gillette, but it was in 1915 that the first women’s razors were created. Hair removal marketing which also began at the same time was mentioning emotions such as shame and fear to persuade females to use the Gillette razors to remove their body hair. Only focusing on the removal of armpit hair in the early advertisements, leg hair removal grew in popularity as women’s dresses began to be shorter and more skin was on show. Phrases indicating body hair to be an embarrassing problem or being hairless a symbol of a modern woman were used to persuade females to remove body hair if they wanted to fit in and be fashionable. In the 1950s, at around the same time as the increased association of pink with femininity, at which point shaving was more widely accepted, adverts promoting body hair removal for women showed messages that indicated being hairless was feminine and classy. Of course, it cannot be forgotten that in the following decades women were encouraged to keep their entire bodies hairless and shaving was seen as something that needs to be done to be perceived as attractive by men. The always growing number of female hair removal products and their gendering design continuously puts pressure on women to remove their body hair if they want to fit into society’s image of being feminine and classy.

When hair removal companies create a ‘problem’ through their advertising, their products can provide a solution, encouraging women to spend money on their hair removal products. Their gendered packaging, some who may consider it attractive, which is often pink, is seen as ‘better’ suited to a female, and customers fall for these marketing tricks, without considering the extra price they are paying just for the colour pink. To answer Pascale Boistard’s question, currently pink is a luxury colour as the evidence shows. Why should women pay for a colour when the same products in more ‘masculine’ hues cost less? What more could be done to stop the Pink Tax? How many more gender inequalities are we going to discover within our designed world?

Please feel free to leave comments in response to this post below. If you would like to contribute a blog post for this series, please contact the DHS Administrator: designhistorysociety@gmail.com. We welcome posts on any place or space from any era, anywhere in the world.

Categories

Contribute

Want to contribute to the blog and newsletter? Contact us

Newsletter

Keep informed of all Society events and activities, subscribe to our newsletter.