Thanks to the DHS Research Publication Grant I was able to include a coloured plate section of forty pages in my new book, Cosmopolitan Radicalism: The Visual Politics of Beirut’s Global Sixties, which has just been published this summer with Cambridge University Press.

Cosmopolitan Radicalism examines the intersections of visual culture, design, and politics in the global sixties. It demonstrates how fluid, yet politically articulated, transnational circuits of modernism converged and contended with one another in the context of Beirut, from the late 1950s to the mid-1970s. Caught between two violent moments in Lebanon’s history, Beirut’s long 1960s was also marked by processes of decolonization and complicated by a Cold War order. Against any celebratory reminiscence of the “golden years”, this book conceives of Beirut’s long 1960s as a liminal juncture, an anxious time and space when the city held out promises at once politically radical and radically cosmopolitan.

Drawing from uncharted archives of everyday printed matter, Cosmopolitan Radicalism is the first historical investigation of graphic design practices from the modern Arab East in academic book form. Shedding light on modes of translocal visuality attached to print technologies, it also critically engages with another similarly ignored facet of Arab postcolonial history: the transnational movement of cultural actors across Arab state borders and the mobility of visual and print cultures. I propose that these cross-border aesthetic practices and mobile cultural artefacts need to be examined outside of nationally circumscribed frameworks. Thus, my analysis situates traveling artists/designers, images/printed objects, political discourses, and aesthetic experiences within the disjunctive cultural flows of the global sixties—at the interface of new modes of consumption and leisure with cultural revolutions, amidst shifting geographies of imperial power and emerging radical forms of resistance, revolutionary anti-imperialism and transnational solidarity.

My focus is on Beirut as a nodal city in the global sixties. In that context, I examine archives of printed matter along with three interrelated themes. The first theme is concerned with the constitution of the city as a Mediterranean site of tourism and leisure within a postwar global economy of travel and consumer desires. Bolstered by development funds and modernization imperatives, this influx drew Beirut into the shadows of US ‘capitalist democracy’ in the Cold War. It draws attention to the historical contingency of cultural practices as ‘Cold War Modernism’ (Crowley and Pavitt, 2008) gets conjugated with the heat of Arab anti-colonial struggles, Lebanon’s 1958 revolt, and subsequent US counterinsurgency campaigns. Seen in this light, the so-called US ‘cultural diplomacy’, I suggest, is a euphemism for more calculated imperialist interventions in a disproportionate geopolitical balance of power, economic and military infrastructure. It is here that a perspective from the global south provides a different optic on the not so ‘cold’ cultural war and one that complicates the binary order of conventional Cold War historiography. Nonetheless, imperialist intentions do not necessarily issue in the desired outcome. My analysis thus shifts focus from global US designs to more nuanced readings of the role of local actors and context.

My second line of enquiry investigates the rise of Beirut as a node of pan-Arab publishing. I explore changes in the visuality and materiality of Arabic cultural periodicals and books in the context of a network of new relations in modern art and literature, printing technologies, the political economy of transnational publishing, and the cultural politics of decolonization in the Arab world.

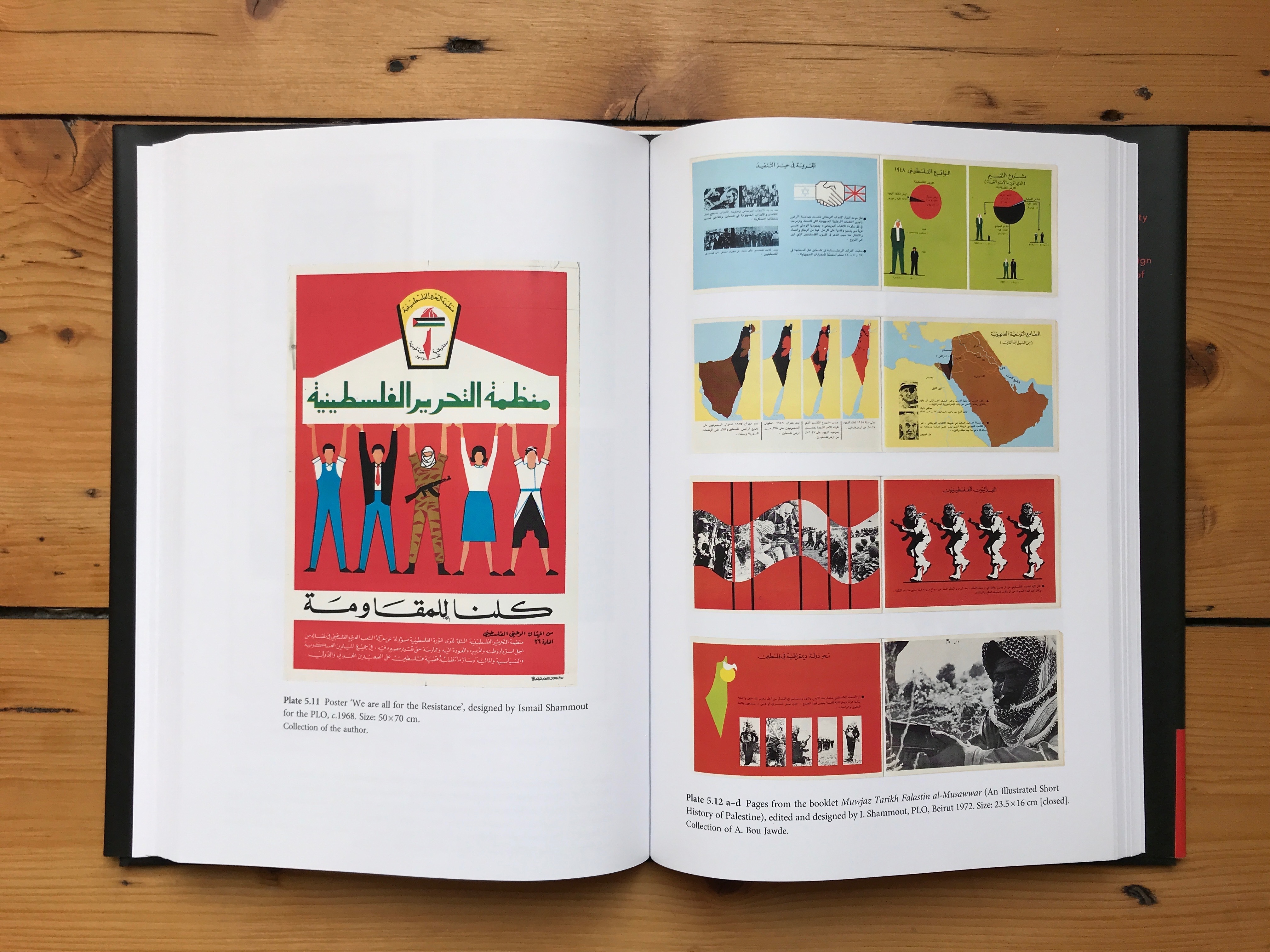

My third strand situates Beirut within a Third Worldist project of anticolonial solidarity and connects it, through the Palestinian Resistance, to an internationalist framework of revolutionary anti-imperialism in the aftermath of the 1967 Arab-Israeli war. I investigate here the translocal visuality of revolutionary struggle in the printscapes of solidarity that marked Beirut’s public culture and street life. The politicization of art at this historical juncture displaced public viewing from the gallery space to the surface of reproducible print—posters, pamphlets, cards, magazines, and books. Militant Arab modernist artists strove to democratize art’s place within society and in doing so hyphenated their art with graphic design practices. Such fluid aesthetic practices reconfigure general perceptions of the relations between the two disciplines, namely of the latter as being the commercial derivative of the former. Rather, graphic design was artists’ tactical alternative to the market system and entry into the public culture and radical politics.

The book reveals how this radical aesthetic configuration developed historically in the interstices, overlaps, and contentions of transnational circuits of modernism, linking Beirut to Cairo, Damascus, and Baghdad among other cities of the Global South during the long 1960s. This nodal configuration decentred Europe from the cosmopolitan imagination and instead engendered radical worldviews stretching their contours from Havana to Hanoi. In all three lines of enquiry and the modernist circuits that traverse these, visuality was increasingly dominant and the demand for graphic design more and more prevalent.

Finally, I hope that this book will contribute to emerging debates in design history around questions of global modernity and transnational modernism, decolonization processes, and art/ design activism, as well as provide useful methodologies for decolonizing design history. I hope it does so while joining in broader discussions about how design shapes our modern everyday life and impinges on society often in mundane and inconspicuous ways.

Dr. Zeina Maasri, University of Brighton

Categories

Contribute

Want to contribute to the blog and newsletter? Contact us

Newsletter

Keep informed of all Society events and activities, subscribe to our newsletter.